I recently finished “Coders at Work“, a series of interviews with famous programmers.

On one hand, reading a book like this is a downer: it’s very clear to me that I occupy a place that is very close to the median of the bell curve, and the skill level of programmers is a very steep non-linear curve in itself. I’ll never be as good as JWZ or Brad Fitzpatrick. But I knew that before, and I am ok with it. On the other hand, this book inspired me to read more code.

The programmers in the book disagree on many points, but they mostly agree on the importance of writing readable code and educating yourself by reading other people’s code. I make my living writing in scripting languages, and I haven’t written a line of C or C++ since college. But there’s nothing preventing me from downloading and taking a look at the source of Apache, PHP, MySQL.

It’s important for me to understand “how the sausage is made” in the PHP stack, and as it turns out, what happens between Apache PHP and MySQL in term of requests and timeouts is not as simple as one might think. I asked at StackOverflow about this, but all the diagrams that people pointed me at were of the very rudimentary type: “look, here’s a happy cow, it goes to Bovine University, look – it’s all shrink wrapped on the supermarket shelf” instead of “sausage farm/slaughterhouse/truck/factory tour, starting with cow insemenation”.

When I downloaded the source code of mod_rewrite, arguably the most useful Apache module in the world, I was amazed to find out that it’s only 5000 lines of C with comments.

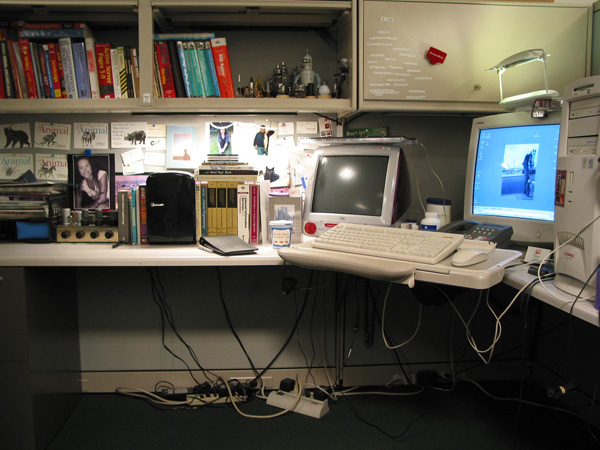

The book ends with the interview of Donald Knuth, and another two major questions that the interviewer is asking everyone is – “have you read Knuth’s books and have you tried literate programming”. It was interesting to find out that most of the famous programmers use Knuth’s the same way that I do. The books sit on my bookshelf, I look at them, I sometimes try to read them, I skip most of the math. They serve as a constant reminder to me that I suck at computer science even more than I suck at programming, and luckily there are people out there who know all of this stuff who are not idiots like me.

Here’s a photo of my cubicle at TV Guide circa 2002, Knuth’s books are holding a place of honor next to the mini fridge. By the way, taking pictures of the places where you work and live is something that you should not forget to do: years from now nobody will care about those pictures of flowers, shadows, and sunsets, but

I’ve read the book about Literate Programming at the time, and was rather inspired by it. Ok, maybe I didn’t read it and more like skimmed it. I don’t think I understood what real literate programming is.

The way I understand it, Literate Programming is a way to write programs as a narrative that is readable to computers and humans. My father, in his former career a site supervisor (a type of a contractor) is very fond of giving very detailed instructions to me, the same way he used to give instructions to construction workers. His instructions usually are exaustive algorithms, with error handling. I think that his instructions, expressed as a flow of conciousness, would work not only on me and construction workers, but on computers as well, and are similar to what Donald Knuth has in mind. All you really have to do is to build a layer of abstraction between these instructions and a computer language. Also, since computers don’t forget things, he would only need to repeat his instructions once.

These days my dad is a COBOL programmer. Everybody dumps on COBOL, but in my mind it’s a language worth of a lot of respect. It has a syntax that is very English-like, something that makes reading COBOL code easy. Well, maybe it’s like reading some old-timer’s newsgroup post written in all caps, but it’s still much closer to English than most other computer languages.

At the time I was reading “Literate Programming” I was using ASP 3.0, IIS, and SQL Server 97. My task was to write a system that would account for booked and pending business. This is something that had to be done since the age of Mad Men. You see, the dealings of clients, account executives (like Pete Cambell), their bosses, account coordinators, creative department, etc are rather convoluted. But in the end, to get paid, you have to have a system that will track who brought in what business, who handled what, and how the commissions need to be split.

This is normally the realm of something called EAS (Enterprise Application Software). Back at the turn of the century, this area was still dominated by a company called SAP, but there were a few smaller players, like Salesforce.com that tried to package these applications. Any sane IT manager looks to see if an EAS solution can be purchased first. It turned out that TV Guide’s buseness logic was impossible to shoehorn into any existing solution. SAP folks said – yeah, no problem, we’ll build you what you want, but our prices start at $1M, and then there are consultant fees. ERM world is a crazy place, you can read about some true craziness in “Cube Farm”, an account of one hapless developer’s adventures at Lawson Software. It’s a truly riveting book, and I fell that every developer out there should read it. It’s literally Lovecraftian in nature, that book.

In any case, it fell to me to develop the application from scratch. Inspired by Knuth, I decided to write some semi-literate code. Me and a project manager, Brad, went to the clients and interviewed them at length, documenting their existing process (aka the most complicated set of spreadsheets you’ve ever seen). In the past, before cheap computers, all you needed was a Joan Holloway, but I believe they stopped making them.

Brad went on to go back and forth with a very terse document about 5 pages in length that described how the new system would work. He would sit down with the clients and go through the narrative, step by step, confirming that this is what they wanted. Meanwhile I created an object oriented library that made dealing with the database, creating forms and navigation elements much easier. This is similar to to what you might find in a CMS like Drupal, only a little cruder.

When the document shaped up, I created the database schema, and then I took a big chunk of the document and pasted it into one huge comment block. I proceeded to break off chunks of that block and writing the code around it. Interestingly enough, as time went on, the project manager started helping me to write the code: enough of scary database abstration was hidden by simple classes and method, and there were tons of self-evident examples all around to copy and paste. I switched to writing reports that involved cubes, rollups and other fancy stuff. Stored procedures that did the reports also received comments from the document that described the reports.

This wasn’t a monolythic system – I was writing it for 2 years or so, releasing a chunk after chunk. In the end it was handed off to another developer, the whole transfer took only a couple of hours. There weren’t any major bugs, maintanence issues (I believe I received only one phone call about it after several years of continuous use). All in all I was pretty pleased with this approach and can absolutely recommend it.

I believe this is the reason why so many English majors become excellent programmers: if you can write for people, you can write for computers. Sometimes there are reasons why you can’t do both at the same time, but there’s no reason not to find some middle ground.