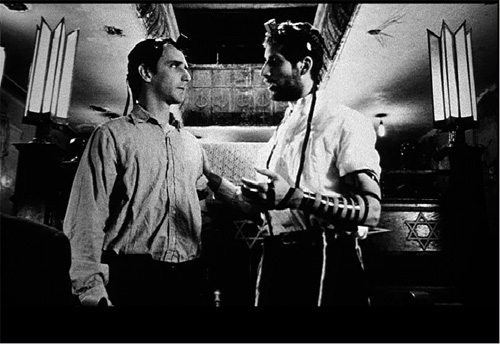

There’s a sequence in Darren Aronofskiy’s “Pi” when the protagonist, mathematician Maximilian Cohen is induced by a Hasidic Jew to on something called Tefillin. Here’s a frame from the movie:

For an ancient Jewish religious artifact, the two black leather boxes and straps used in prayer, are very strange looking and science-fictiony. I decided to do a bit of research on them, and came upon a lot of very interesting stuff. I’ve made a lot of notes, but for years I did not have the time to sit down and actually write this post.

Tefillin is a very curious Jewish religious artifact, similar to a few others, such as Sefer Torah and Mezuzah. What they have in common is the exactitude in which they reproduce holy texts in hand-written form.

Scott Adams nicely summarized the problem of propagating holy writing in his recent post:

I never knew that there are about a zillion different versions of the Bible because (and I am summarizing Ehrman’s entire book here) it was copied and recopied by hand, by semi-literate, opinionated morons for hundreds of years. Sometimes the copiers left stuff out, sometimes they added their own explanations where things didn’t seem to make sense, and other times they simply made errors.

This, of course, brings to mind the old joke about a novice monk who asks his superior about the possibility of mistakes in the holy books that the monks in his monastery have been copying by hand for centuries. The head monk goes to check the originals hidden away in a vault. Having not heard from him for days, the novice monk goes to check on the old monk and finds him hunched over the old books crying and saying the same phrase over and over. “The word is ‘celebrate‘ !”

The Hasidic Jew from “Pi” was a Torah numerologist. See, the Torah is considered to be the literal word of God as given to Moses, exact to a letter. Hebrew letters have numerical values, so Torah can be treated as a string of numbers that might contain hidden patterns, encoded messages, maybe even computer code. Exactitude is very important here – a single letter might change everything, like in a computer program or a cyphered message. Or like removing the letter “r” from the word “celebrate”.

The practice of using Tefillin comes from a literal understanding of a passage in the Torah, Deuteronomy 6:8.

“And these words, which I command thee this day, shall be in thine heart:

…

And thou shalt bind them for a sign upon thine hand, and they shall be as frontlets between thine eyes.”

What seems to be a poetic metaphor about the importance of the holy writing, is taken literally here, prompting the creation of an artifact consisting of two black leather boxes containing scrolls with passages from the Torah to be worn bound to a hand and forehead with leather straps.

If you’ll go shopping for a set of Tefillin, you might be surprised at how much they cost. The cheapest set from a reputable place will set you back at least several hundred dollars, with better made ones costing in the thousands of dollars. Why? Because of the excruciatingly exact way they are supposed to be made.

The leather cases and straps need to be made from Kosher parchment and to pretty exact specifications. The cheaper ones are made from glued pieces of leather, the more expensive ones are made out of single pieces of leather, either folded using what one website calls “Jewish origami” or pressure-molded by special presses. The latter are considered more kosher.

But the cases are a small part of the value of the Tefillin. The handwritten scrolls are what’s expensive. Scribes (Sofer) who are qualified to make kosher Tefillin are few and far between, and not only because they are supposed to a God-fearing, religious Jews of high moral fibre. The letters on the scrolls are small, but have to be perfectly formed in a rather complicated font, of which there are several varieties. There can’t be a single mistake, not even in a part of a letter.

There are certain prayers that have to be said. Letters have to be written in a precise order. They can’t touch each other, holes or edges of the parchment. Parts of the letters can’t be erased and they have to be perfectly formed. The parchment has to be properly prepared, a proper quill pen and specially formulated ink has to be used.

These are just some basic rules that I gleaned from various websites. Apparently they rules are so complicated that even experienced scribes are sometimes baffled at subtleties of writing these scrolls. When in the middle of a laborious process of writing a scroll, they sometimes come to consult a specialist called a posek rather then throwing away their work and starting anew. Even a specialist is sometimes not sure if a letter is correctly formed. What happens then is rather interesting:

“Shailos tinok is a query presented to a child. Occasionally a posek will be in doubt how to render a decision, psak. […] He will suggest that a child […] who knows the letters of the Aleph – Bais but has not yet learned to read, be asked. Such a child sees nothing other than the form before him and can judge without any influences.”

There are literally thousands of ways in which the tiniest imperfection can completely invalidate a Tefillin. And religious Jews take this commandment very seriously, so making of Tefillin is in no danger of being outsourced to China despite the high availability of good calligraphers there.

There’s even a dispute as to in what order the scrolls need to be put into the cases. Most rabbis agree, but still, there are some who put two pair of Tefillin at once, made in two different ways. Kind of like Ned Flanders who “kept kosher just to be on the safe side”.

On the cynical side, there’s a phenomenon referred to as “Tefillin date”. Some hypocritical Jews take their Tefillin with them when they go on a date, planning to spend the night, and while breaking the pretty clear “no sleeping around” rule, not breaking “pray with Tefillin in the morning” rule.

Sefer Torah is a full length Torah (about 300,000 letters) written on a scroll in to specifications that are similar to the making of Tefillin. While writing Tefillin scrolls might take experienced scribe 2-3 days, Sefer Torah is often a lifetime project. Their cost ranges from tens of thousands of dollars to millions of dollars.

This exacting standard of copying is what made the modern Torah scrolls match almost exactly the texts dating back to before 100 BC found in the Dead Sea scrolls.

If you ever lived in New York City, you must have seen a mezuzah, the third and simplest of the Torah scroll artifacts. It comes from a literal understanding of Deuteronomy 6:9

“And thou shalt write them upon the posts of thy house, and on thy gates.”

Mezuzah takes a form of a decorated case containing a scroll nailed to a doorpost. On almost every floor of almost every apartment building in New York you’ll find at least one door with a mezuzah. In some, like in mine, almost every door has one. The variety of the decorative cases is astounding. There are big ones, small ones, ornate ones, simple ones. They are made of plastic, wood, metal. Most are left by tenants of long ago. Many are painted over. In many cases I see voids in paint where mezuzah used to be.

The one left to me seems somewhat old, probably left by the original owners of the apartment. On the back it has the original orange paint which is not out of character for my Art Deco building. I bet it dates to the 50s or 60s (can’t be much older than that because it’s “Made in Israel”).

What makes it absolutely invalid, of course, is the lack of the handwritten scroll inside. In fact, this is the case with most mezuzot you’ll find in New York. The case might be pretty, but the scroll inside takes at least a few hours of scribe’s work and costs from 30 to 100 dollars.

Even though I am not an observant Jew, one of these days I’ll replace my mezuzah case with a titanium one and buy a real scroll. Also, I want to put on a Tefillin once. All I have to do is find the nearest mitzvah tank, but Hasidim make me feel uneasy.